He's the real thing: how Shakespeare

influenced the American ad industry

From

Abraham Lincoln to Coca-Cola, the Folger Shakespeare Library shows how the Bard

and his plays became embedded in American history and advertising

A

handsomely bound complete works of William Shakespeare stands upright beside

opera glasses, a blue lace handkerchief and a single rose. On the wall is a

picture of President Thomas Jefferson’s house Monticello

and an article torn from a newspaper about an “All-American football team”. And

also visible is a red badge that says “Coca-Cola 5c”, an open bottle of Coke

and a big silhouette of a girl drinking the same. The caption says: “Thirst,

too, seeks quality.”

Shakespeare

meets Mad Men in this display of how the American advertising industry deployed

the Bard of Avon to add a touch of class to the postwar consumer boom. The 1949

Coke ad is among an array of beguiling cultural artifacts now on show in America’s Shakespeare at the Folger Shakespeare

Library in Washington DC, coinciding with the imminent 400th anniversary of the

playwright’s death.

As

she put the finishing touches to the exhibition on Wednesday, curator

Georgianna Ziegler looked at the Coca-Cola ad and remarked: “Isn’t that

interesting as a cultural moment, bringing all these things together: Coke is

popular but it’s also classy; it can be enjoyed by people who go to opera and

people who go to football; it’s also very American. I think that’s a

fascinating piece of advertising. It says a lot about what people saw as the

role of Shakespeare in American society.”

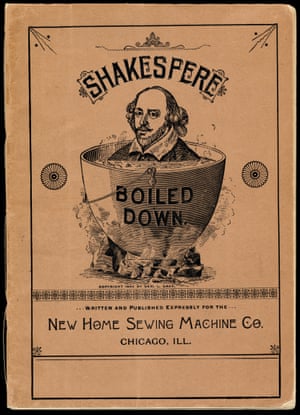

As

if to prove the old adage that the chief

business of the American people is business, Shakespeare has

appeared as a salesman thousands of times, the exhibition notes, pushing

everything from sewing machines to cigars to Levi’s, from fishing reels, beer

and whiskey to cough syrup, cars and mobile phones.

Indeed,

the first reproduction of Shakespeare’s image to appear in America was in an

advert: an engraving based on his statue at Westminster Abbey used to promote a

stationery company in Philadelphia. It ran in a 1787 volume of the Columbian

Magazine that contained articles such as “A letter in praise of laughter”, “A

Whimsical Solution to the Ancient Problem of Prometheus” and “Verses by a

French Gentleman Addressed to his Bed”. It is also on display at the Folger.

“I

speculate that Shakespeare was a sign of class and elegance – that is the

raison d’être behind most of the adverts using him,” Ziegler said. “Shakespeare

was something a lot of people knew at that time; it was part of everyday life.

They weren’t studying him in school so much, but they were memorising speeches:

elocution was a big thing.”

The

exhibition’s touchscreens include various TV ads, most recently from Under

Armour sports clothing whose commercial last year “Shakespeare

Got it All Wrong”. In a rebuttal to “All the world’s a stage, and

all the men and women merely players,” actor Jamie Foxx declares: “Mr

Shakespeare never met Stephen Curry,” describing the basketball star as a “new

creative genius” and “patron saint of the underdog”.

America’s

fascination with Shakespeare is older than the republic itself. One of the

prize exhibits is a new acquisition, the earliest documented ownership of a

Shakespeare folio in the New World. It is listed on a blank page in a 1673

English translation of Juvenal that belonged to Major Edward Dale, a royalist

who fled to America after the English civil war.

As

the colonists rebelled against British rule and its punitive taxes, leading to the revolutionary war, both sides reached for

Hamlet. “Be taxt, or not be taxt, that is the question,” wrote a patriot in

1770, while a loyalist Tory expressed uncertainty about whether to subscribe to

a boycott of British goods in 1774: “To sign, or not to sign? That is the

question.”

Likewise

soldiers on both sides of the American civil war performed his plays in between

battles. The exhibition includes an 1864 photo and New York playbill for Julius

Caesar starring John Wilkes Booth and his two brothers to raise funds for a

Shakespeare statue in Central Park. Six months later, Booth shot Abraham Lincoln at Ford’s Theatre in

Washington and, the display shows, posters announced the president’s death with

quotations from Macbeth.

A collectible card issued by Liebig’s Extract of Meat

Company portrays a scene from Shakespeare’s play Macbeth. Photograph: Folger

Shakespeare Library It was a work that both men particularly admired. “I

think none equals Macbeth,” wrote Lincoln, who often quoted the playwright, in

a letter also on public view. As Booth fled into hiding, he also quoted from

the Scottish play in the last words of his diary: “I must fight the course.

’Tis all that’s left in me.”

German,

Irish, Italian and Russian immigrants put their own spin on the Bard, but

African American actors Ira Aldridge and Paul Robeson were forced to

develop their careers in Europe. Shakespeare’s plays were raw material for

hundreds of silent films, with Richard III (1912) the first full-length

feature; actor Frederick Warde often appeared at screenings and read extracts

from the play during the changing of the reels. Then came gloriously American

musical takes on the canon such as Kiss Me Kate and West Side Story.

When

television arrived, the DuMont network came up with the strapline:

“Verily Mr Shakespeare. All the world’s a stage … with television.” Ziegler

observed: “Every time a new medium was introduced, Shakespeare was there. It

made this new media OK because you can do what Shakespeare did.”

The

exhibition includes cartoons, promptbooks, radio broadcasts and theatrical

costumes. Perhaps the unlikeliest photo is of an American soldier in Vietnam

with a copy of The Taming of the Shrew strapped to his helmet. An “Armed

Services Edition” of Henry V was put out for the second world war

and reprinted for troops in Iraq.

Created

by oil tycoon Henry Clay Folger and his wife Emily, the library has the world’s

biggest Shakespeare collection and a working theatre. Ziegler, its associate

librarian and head of reference, recalled that in pre-internet days she would

often get calls from the nearby Congress asking for Shakespearean quotations to

leaven political speeches. “I remember Al Gore’s

office called asking for a quotation from Coriolanus. I said, ‘what about?’,

but they wouldn’t tell me. I don’t know if they ever used it.”

Shakespeare

in America is one of the subjects considered in Andrew Dickson’s book Worlds Elsewhere: Journeys Around Shakespeare’s Globe.

He said on Thursday: “One of the fascinating things about American Shakespeare,

particularly during the 19th and early 20th centuries, is how the plays come to

saturate culture at every level, from east coast libraries and reading

societies to minstrel shows and advertising hoardings.

“For

advertisers in particular it’s a way of showing off your sophistication – if

you’re smart enough to have brushed up on your Shakespeare, you’re smart enough

to buy our product. My own favourite is a Ford ad from 1964 called ‘Seven

Characters in Search of Seven Cars’, which suggests that the perfect car for

Cleopatra is a Capri. Prospero from The Tempest only gets a Cortina, which

sounds a bit of a raw deal.”

No comments:

Post a Comment