Dominic Monaghan joins Shakespeare horror anthology series ‘A Midsummer’s Nightmare’

“It will have blood. They say, blood will have blood.”

Things are about to get even bloodier than Shakespeare’s bloodiest revenge stories, and Dominic Monaghan is on board. The Lost and Lord of the Rings alum has signed on for a role in Lifetime’s horror anthology take on the Bard’s plays.

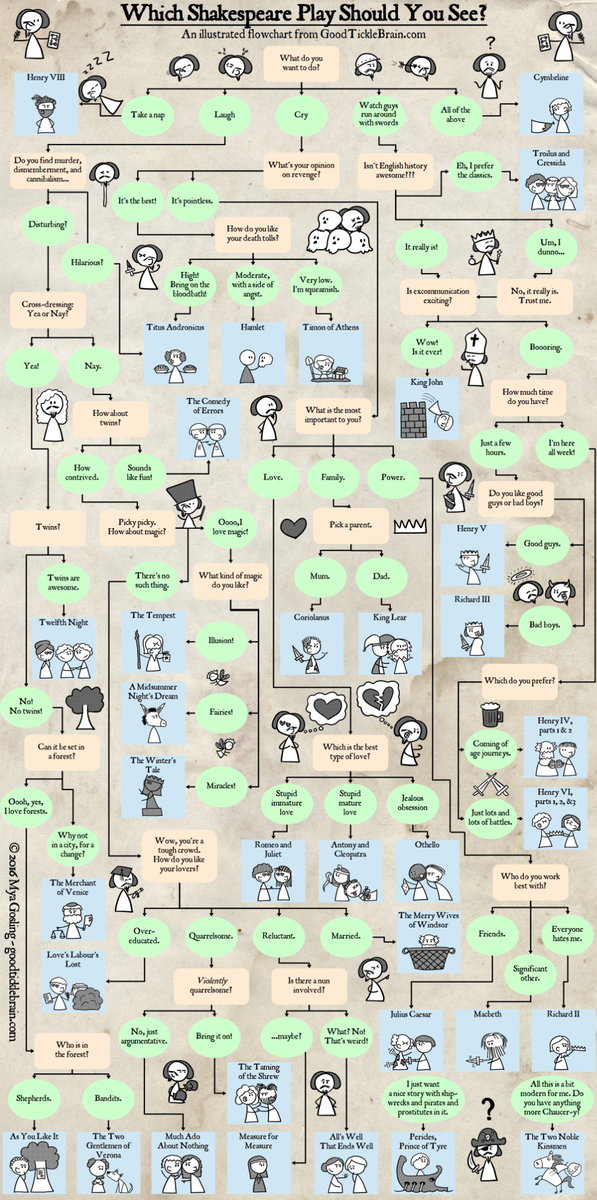

There’s certainly plenty in Shakespeare that lends itself to horror — Macbeth and Titus Andronicus come to mind — but Lifetime is turning to a comedy play for its first season: A Midsummer Night’s Dream. The anthology series itself is titled A Midsummer’s Nightmare.

Monaghan is playing the show’s version of Puck. The Brit best known for playing a mischievous hobbit seems like a solid fit for Robin Goodfellow. In this interpretation, Puck is “Mike Puck,” according to Deadline, “the laid-back and well-spoken proprietor of the Dreamland Retreat, a rustic group of rental cabins in the woods. Although initially suspicious of his young guests, Puck becomes a formidable ally when things start to go awry.”

Anthony Jaswinski, who wrote this summer’s The Shallows, is adapting Shakespeare’s Midsummer for the series. Along with the addition of Monaghan to the project, Jaswinski is joined today by Gary Fleder (Zoo, Kingdom), who will direct the pilot and executive produce the series.

Here’s how Lifetime described the series earlier this year:

Variety reported

that the plays are turned into “contemporary horror mysteries,” so I’m

assuming Lifetime will set the series in modern day with language not in

verse. (Maybe they’ll find that earlier eras lend themselves to horror

interpretations of some plays, though, just as American Horror Story has set each of its cycles in a different time and place.) So Monaghan won’t need any advice from his LotR

buddy Billy Boyd about taking on the Bard’s verse, but perhaps he and

Boyd will still find themselves comparing notes on Shakespeare sometime

(Boyd played Banquo in a 2013 production of Macbeth at the Globe).

I’d like to see the inherent horror elements of The Scottish Play and Titus ramped up for this series. Caliban in The Tempest too could give us a striking horror fantasy. Hamlet is psychological thriller-ready. But I’m also intrigued by the possibilities of adding horror elements to other plays. Perhaps a Comedy of Errors where all the misunderstandings and mistaken identity make for gory tragedy instead of humorous reunions. Or an alternate take on The Merchant of Venice where Portia never makes it to court and we do see a pound of flesh cut from Antonio.

Interesting question here: Can a Midsummer’s Nightmare finale give us a happy ending? Will a comedy-based play still end in a wedding? Or will a final girl be the only one who makes it out of Dreamland Retreat? So long as the project gets a series order, I suppose we’ll find out once Midsummer’s Nightmare makes its debut on Lifetime.

Things are about to get even bloodier than Shakespeare’s bloodiest revenge stories, and Dominic Monaghan is on board. The Lost and Lord of the Rings alum has signed on for a role in Lifetime’s horror anthology take on the Bard’s plays.

There’s certainly plenty in Shakespeare that lends itself to horror — Macbeth and Titus Andronicus come to mind — but Lifetime is turning to a comedy play for its first season: A Midsummer Night’s Dream. The anthology series itself is titled A Midsummer’s Nightmare.

Monaghan is playing the show’s version of Puck. The Brit best known for playing a mischievous hobbit seems like a solid fit for Robin Goodfellow. In this interpretation, Puck is “Mike Puck,” according to Deadline, “the laid-back and well-spoken proprietor of the Dreamland Retreat, a rustic group of rental cabins in the woods. Although initially suspicious of his young guests, Puck becomes a formidable ally when things start to go awry.”

Anthony Jaswinski, who wrote this summer’s The Shallows, is adapting Shakespeare’s Midsummer for the series. Along with the addition of Monaghan to the project, Jaswinski is joined today by Gary Fleder (Zoo, Kingdom), who will direct the pilot and executive produce the series.

Here’s how Lifetime described the series earlier this year:

An anthological concept where each season takes a classic Shakespearean tale and twists it into a modern-day horror-mystery. A Midsummer Night’s Dream

inspires the first season as two young lovers escape their lives on a

romantic getaway into the woods until their journey takes an unexpected

twist when their friends arrive trying to lure them back home. Something

hiding in the forest has other plans, however, and they are targeted

one by one while a thrilling and desperate tale of survival unravels.

I’d like to see the inherent horror elements of The Scottish Play and Titus ramped up for this series. Caliban in The Tempest too could give us a striking horror fantasy. Hamlet is psychological thriller-ready. But I’m also intrigued by the possibilities of adding horror elements to other plays. Perhaps a Comedy of Errors where all the misunderstandings and mistaken identity make for gory tragedy instead of humorous reunions. Or an alternate take on The Merchant of Venice where Portia never makes it to court and we do see a pound of flesh cut from Antonio.

Interesting question here: Can a Midsummer’s Nightmare finale give us a happy ending? Will a comedy-based play still end in a wedding? Or will a final girl be the only one who makes it out of Dreamland Retreat? So long as the project gets a series order, I suppose we’ll find out once Midsummer’s Nightmare makes its debut on Lifetime.

An enthusiast of time travel stories, film scores, avocados and

Charades, Emily Rome is an alumna of Loyola Marymount University and a

native of beautiful Washington State. Emily’s writing has also appeared

in the Los Angeles Times, Entertainment Weekly and The Hollywood

Reporter. Follow her on Twitter @EmilyNRome.